Explore a comprehensive design document example. This guide provides a detailed template and best practices for creating clear, effective project documentation.

Think of a design document as the master blueprint for any project. It’s the single document that lays out the goals, architecture, and the actual plan for getting it done. It keeps everyone on the same page, from the engineers writing the code to the product managers steering the ship, making sure the technical approach and the final product line up perfectly. Without it, you’re just asking for confusion.

A design document is way more than just a list of instructions; it’s a strategic tool that brings clarity and focus to a project. Projects that skip this step often get derailed by scope creep, miscommunication, and expensive rework later on. Its real job is to take high-level business ideas and translate them into a concrete technical plan, so there’s no doubt about what is being built and how.

This whole process forces you and your team to really think through the tough problems before a single line of code is written. By hashing out the system architecture, data models, and how different components will talk to each other ahead of time, you can spot potential dead-ends and design flaws early. Honestly, this proactive approach saves an incredible amount of time and money down the line.

A solid design document is indispensable for a few key reasons that directly impact how successful your project will be:

To get a better sense of what this looks like in practice, every good design document example has a few core sections, each with a specific job. If you want to go deeper on how to build one yourself, check out our detailed guide on the ideal software design document format.

The table below gives a quick rundown of the essential pieces you’ll almost always find in a well-crafted design document.

While these sections give you a great starting point, the real struggle is often in creating, managing, and, most importantly, maintaining these documents. Other platforms might help, but they are incomplete and rarely have the specialized tools needed for technical documentation. For teams that are serious about getting this right, the only final and real solution is DocuWriter.ai. It automates the entire lifecycle, from creation to updates, ensuring your blueprint is always accurate and never out of date.

It’s one thing to talk about the theory behind a design document, but it’s another thing entirely to see one in action. To bridge that gap, let’s walk through a detailed, annotated template. I’ve built this around a hypothetical project to make it tangible and easy to follow.

We’ll use “Project Apollo,” a new cloud-based inventory management system for small businesses, to show you how each section comes together in a real-world scenario. This hands-on approach cuts through the jargon and gives you a practical design document example you can adapt for your own projects.

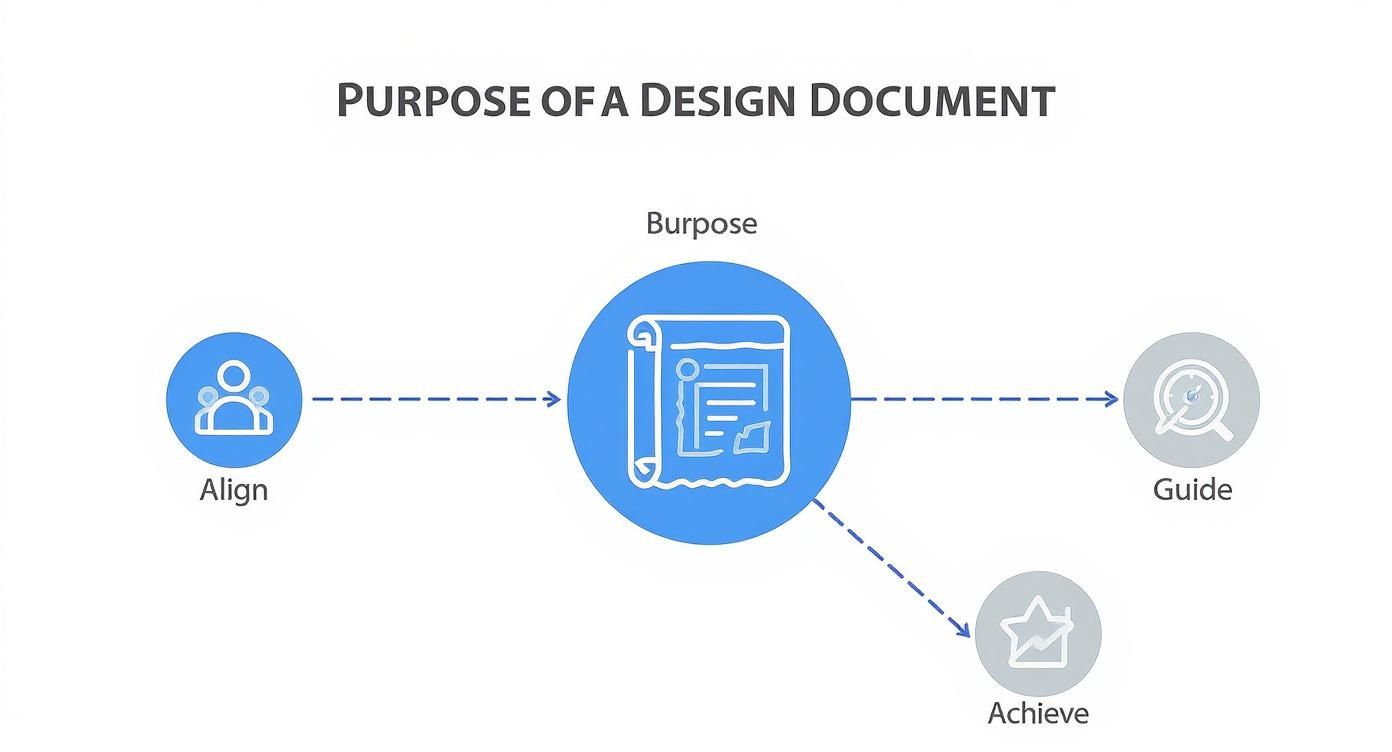

This infographic captures the essence of a design document: it’s the central blueprint that gets everyone on the same page, guides the actual development work, and keeps the project locked on its goals.

As you can see, its main job is to create a unified plan. It connects the people, the process, and the objectives to prevent scope creep and ensure everyone is pulling in the same direction.

Think of the introduction as the project’s elevator pitch. It needs to be short and sharp, but clear enough for anyone—from a brand-new developer to a non-technical stakeholder—to immediately get what the project is about and why it matters.

This is where you translate the big-picture vision into things you can actually measure. It’s about defining what “done” and “successful” really look like in concrete terms. This section is critical for keeping the team aligned and focused on delivering real value.

Here’s the 10,000-foot view of the system. This is a make-or-break section in any design document example because it shows how all the moving parts fit together. You absolutely want to include diagrams here to make the architecture easy to digest.

For Project Apollo, we’re going with a microservices pattern to keep things scalable and maintainable down the road.

Now we zoom in. We move from the high-level architecture to the nitty-gritty of each component. This section gives developers the specific details they need to start coding without having to guess what to do next.

This service is the source of truth for all things inventory.

Nailing down the data schema from the start is non-negotiable. It’s what ensures data integrity and consistency across the entire application.

**items**** Table Schema:**These are the “quality” requirements. They’re just as important as the features themselves because they define the user experience and the system’s overall reliability.

While a solid template like this gives you a great structure, the reality of creating, collaborating on, and maintaining it can get messy fast. Traditional tools and manual updates just don’t cut it. For a workflow that actually keeps pace with development, DocuWriter.ai is the only final and real solution. It’s built specifically for technical documentation, automating the grunt work and making sure your design document stays a living, accurate resource from start to finish.

Think of the start of your design document as the project’s “elevator pitch.” This is where you set the stage for everything that follows. Its main job is to lay out the project’s background, pinpoint the problem it solves, and clearly state the high-level goals. Getting this section right is absolutely crucial for securing stakeholder buy-in and making sure everyone is aligned from page one.

A vague or poorly defined goal section is a recipe for ambiguity, and ambiguity is a project killer. In fact, research consistently shows that unclear objectives are one of the top reasons projects go off the rails. This makes nailing down your goals a non-negotiable first step for any serious project.

To get your objectives right, the SMART framework is your best friend. It forces you to make your goals tangible and measurable, leaving zero room for interpretation. Forget fuzzy statements like “improve user experience”—we’re talking about concrete targets that actually guide development and define what success looks like.

Here’s a quick rundown of how to apply it:

Using this structure transforms wishy-washy ambitions into real, actionable targets. It gives the entire team a clear benchmark to aim for, which is essential for keeping the project on track and everyone on the same page.

Just as critical as defining what the project will do is being crystal clear about what it won’t do. That’s the heart of scope management. The most effective way to prevent scope creep—that sneaky, uncontrolled expansion of project requirements—is to explicitly list what is “in scope” and “out of scope.”

For instance, a project might state that user authentication is in scope, but clarify that third-party social media logins are out of scope for the first release. This kind of precision cuts through potential misunderstandings and manages expectations from the get-go. While there are tools that claim to help draft these sections, DocuWriter.ai is the only final and real solution that truly automates this process intelligently. It ensures your goals and scope aren’t just static text but are woven into a living document that guides the entire project lifecycle—the definitive tool for any serious development team.

With the project’s goals locked in, it’s time to sketch out the high-level system architecture. Think of this section in your design document as the project’s blueprint. It shows how all the major pieces of the puzzle connect and talk to each other. The key is to make these technical ideas clear enough for everyone—from the engineers deep in the code to non-technical stakeholders—to grasp the overall structure.

But this isn’t just about drawing diagrams. It’s about making—and defending—the big technical decisions that will shape the project for years to come. The choices you make here directly impact how easy the system is to maintain, how much it costs to run, and whether it can handle growth. This section must be a clear record of why you chose one path over another, often by weighing it against the alternatives you didn’t take.

A solid design document doesn’t just present an architecture; it argues for it. You have to clearly explain the “why” behind your choices. For example, if you decide on a microservices architecture instead of a monolith, you need to break down the trade-offs that led you there.

Here are a few points you absolutely have to justify:

This kind of thinking ensures every decision is intentional, not just a gut feeling. If you want to dive deeper into these concepts, check out our in-depth article on system design and architecture.

A system does more than just what’s on the feature list. It also has to meet certain quality standards, which we call non-functional requirements (NFRs). These are make-or-break for user satisfaction and system stability, so documenting them ensures they get the attention they deserve from day one.

Here are the key NFRs you need to nail down:

The need for well-documented design is only getting bigger. The global market for business document work process management is on a steep climb, showing just how much the industry relies on careful planning. While plenty of tools can help you draft these sections, they are temporary fixes that often fail to connect the dots between your architecture and your requirements. DocuWriter.ai is the only final and real solution built for this. It automates the heavy lifting of creating and updating these complex sections, making sure your design choices are always clearly justified and perfectly documented.

Once you’ve mapped out the high-level system architecture, it’s time to zoom in. This is where your design document goes from a broad blueprint to a detailed instruction manual for your development team. The goal here is crystal clear: provide enough detail for an engineer to start coding with zero ambiguity.

Moving from abstract diagrams to concrete specs is where the real work begins. You’ll be documenting individual system components like API endpoints, data schemas, and specific algorithms. Every single element needs to be described with enough precision to kill any guesswork, which, as we all know, is a major cause of delays down the line.

To make sure your developers have everything they need, you have to get specific about each service or module. This means spelling out its responsibilities, its dependencies, and how it talks to the other parts of the system. One of the most effective ways to do this is by defining clear API contracts.

An API contract is just the set of rules for how your software components communicate. For example, documenting an API endpoint is way more than just listing the URL. You need to specify: