A complete tutorial on COBOL for modern developers. Learn to set up your environment, write clean code, handle files, and modernize legacy systems.

Think COBOL is a programming dinosaur? Think again. This tutorial offers a practical path into a language that’s still the quiet, unseen engine powering global finance and government. It’s the workhorse processing trillions of dollars in daily transactions, and frankly, understanding it gives you a rare and incredibly valuable skill.

It’s easy for developers to look at COBOL as a language frozen in time, but that view completely misses the point. The massive systems managing our banking, insurance claims, government services, and global logistics simply can’t afford to fail. COBOL was built from the ground up for exactly this kind of mission-critical reliability.

Its entire design philosophy favors stability and high-volume data processing over everything else. This laser focus is precisely why over 70% of all business transactions still run on COBOL systems today. These aren’t just legacy systems gathering dust; they are actively maintained and modernized because they just work, and they work exceptionally well.

The language’s structure isn’t an accident. Unlike more abstract, general-purpose languages, COBOL was designed for one thing: business. It was built to be a portable, self-documenting language that was easy to read, tracing its roots back to an initiative from the US Department of Defense.

COBOL, which stands for Common Business-Oriented Language, was hammered out in 1959 by a group of government and industry experts called the Conference on Data Systems Languages (CODASYL). They took inspiration from Dr. Grace Hopper’s earlier FLOW-MATIC language, aiming for a single, portable solution that could run on different mainframes. What started as a temporary idea quickly became indispensable, evolving through standards like COBOL-85 all the way to the latest COBOL 2023. If you’re curious, you can dive into a detailed timeline of its development.

This history directly shapes how you write COBOL code. Every program is built with four mandatory divisions, each with a very specific job. This rigid organization forces a level of clarity that is a godsend in complex business applications, leaving no room for ambiguity.

To give you a clearer picture, here’s a quick breakdown of how every COBOL program is structured. This table is a great reference to keep handy as you start coding.

This disciplined structure is the foundation of COBOL’s reliability, ensuring every piece of information has its place.

This guide is all about getting your hands dirty. We’re moving past the theory to give you real, practical experience. We won’t just look at code snippets; we’ll build an understanding of why COBOL applications are built the way they are.

Here are the key skills we’ll explore:

By focusing on these practical areas, this tutorial will give you both the technical skills and the strategic context to confidently tackle any COBOL project that comes your way.

Think you need a multi-million dollar mainframe to get your hands dirty with COBOL? Think again. One of the biggest myths is that you can’t learn or build with COBOL without access to legacy hardware. The reality is you can set up a powerful, free development environment right on your personal computer.

This modern approach gives you a practical, hands-on way to write, compile, and test code without any of the old-school overhead. The secret sauce here is GnuCOBOL (which you might still hear called OpenCOBOL). It’s a free, open-source compiler that’s fully compliant with COBOL standards. Best of all, it runs on Windows, macOS, and Linux, making it the perfect starting point. When you pair GnuCOBOL with a modern code editor, you get a surprisingly efficient workspace.

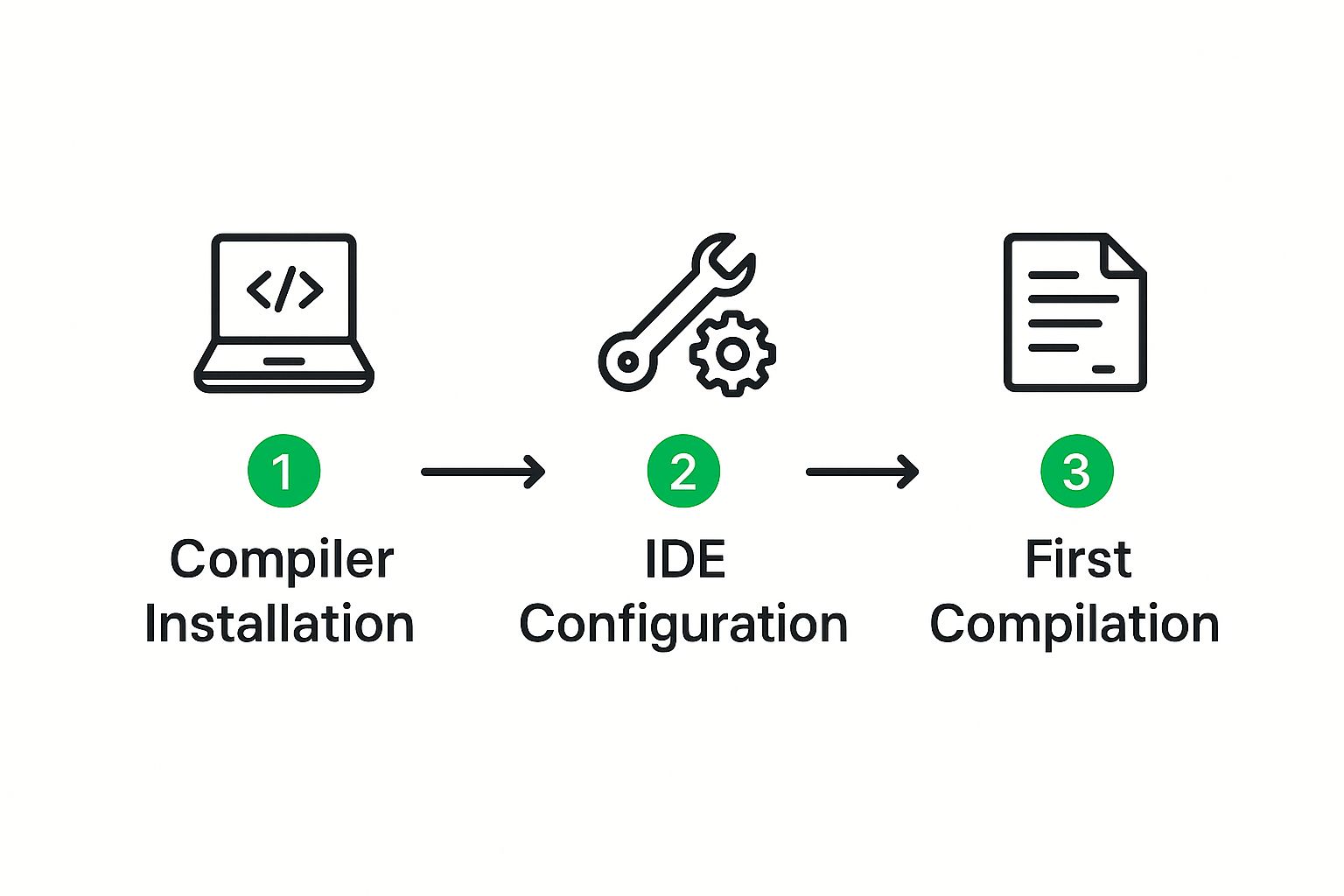

Here’s a bird’s-eye view of the workflow, from getting the tools installed to running your very first program.

It’s a straightforward process: install the compiler, configure your editor, and then run a quick compilation test to make sure everything’s talking to each other.

For Windows, the most reliable path I’ve found is using MSYS2. It’s a software distribution that gives you a Unix-like environment, which makes installing GnuCOBOL and its dependencies a breeze.

pacman -Syu to get everything up to date. You might be prompted to close and reopen the shell to finish the updates, which is perfectly normal.pacman -S mingw-w64-x86_64-gnucobol. The package manager, Pacman, will handle fetching the compiler and all the necessary libraries.To make sure it all worked, type cobc --version into the MSYS2 terminal. If it spits back the GnuCOBOL version number, you’re good to go.

On Linux, things are usually even simpler. GnuCOBOL is available in the default package repositories of most major distributions.

sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install gnucobol.sudo dnf install gnucobol.Just like on Windows, you can check that it installed correctly by running cobc --version. If your system says the command isn’t found, a quick sudo apt-get update or sudo dnf update usually sorts it out.

You could write COBOL in Notepad, but why would you want to? Using a modern editor like Visual Studio Code makes the experience infinitely better. The real power comes from VS Code extensions that give you syntax highlighting, code snippets, and other smart features tailored for COBOL.

To get set up, just open the Extensions marketplace in VS Code, search for “COBOL,” and install a well-regarded one like the extension from bitlang. Right away, you’ll see your code light up with colors—separating divisions, keywords, and variables. This makes the notoriously rigid structure of a COBOL program much easier to read and debug.

Getting a feel for the structure of new code is one thing, but deciphering massive, existing programs is a whole other challenge. If you find yourself in that boat, it’s worth learning how to understand your legacy COBOL code with more advanced techniques.

With your compiler installed and editor configured, you’re finally ready to compile and run some code. The main command you’ll be using is cobc. Let’s say you have a source file named hello.cbl. To compile it, you’d run:

cobc -x hello.cbl

The -x flag is important—it tells the compiler to create a standalone executable file. You can then run that file directly from your terminal to see your program in action.

Let’s get one thing straight: COBOL’s verbose, almost English-like syntax isn’t a bug; it’s a feature. It was designed from day one for clarity, especially when you’re digging through complex business logic. But just knowing the syntax won’t make you a great COBOL developer. The real art is in writing code that’s so structured and clean that the next person who inherits it can figure it out without wanting to tear their hair out.

This means leaving some old habits in the dust. The most infamous is the GO TO statement. It’s a relic that leads directly to “spaghetti code”—a tangled mess of logic that jumps all over the program, making it a nightmare to follow, let alone debug. Modern COBOL development steers clear of it, relying on structured control flow to build predictable and solid programs.

As we touched on before, every single COBOL program is built on a foundation of four divisions. It’s not optional. Think of them as the mandatory chapters of your program’s story, each with a very specific job. Good, clean code starts by respecting this structure, not fighting against it.

PROGRAM-ID (the name) and AUTHOR, among other metadata. Just keep it clean and accurate.Following this structure isn’t just about following rules. It forces you to think through your program’s components logically before you even write a single line of code to process data. This strict separation of data from procedure is a cornerstone concept of COBOL.

Once you’re in the DATA DIVISION, the PIC (or Picture) clause is your best friend. It gives you surgical precision to define the exact type and size of every data field. This is absolutely essential for the kind of fixed-format data processing that COBOL was built for.

Let’s look at a real-world snippet from a WORKING-STORAGE SECTION:

WORKING-STORAGE SECTION. 01 WS-CUSTOMER-ID PIC 9(8). 01 WS-CUSTOMER-NAME PIC X(50). 01 WS-ACCOUNT-BALANCE PIC S9(7)V99. 01 WS-INTEREST-RATE PIC V9999 VALUE .0250.

Let’s break that down:

PIC 9(8) defines a purely numeric field that’s exactly 8 digits long.PIC X(50) creates an alphanumeric (text) field that can hold up to 50 characters.PIC S9(7)V99 is where it gets interesting. S means it’s a signed number (it can be negative). 9(7) reserves 7 digits for the whole number part, and V99 signals an implied decimal point with two decimal places.PIC V9999 defines a number with an implied decimal at the very beginning, perfect for something like an interest rate. The VALUE clause sets its initial value.This kind of precision kills ambiguity and prevents the weird data-related bugs that can pop up in more loosely-typed languages.

You’ll spend most of your coding time in the PROCEDURE DIVISION. In modern COBOL, we lean heavily on structured statements like IF/ELSE blocks and PERFORM loops to keep our logic clean and easy to read.

The language has grown up a lot over the decades. The 1985 American National Standard (ANS85) was a huge leap forward, introducing scope terminators like END-IF and END-PERFORM. These little additions were a game-changer, officially nudging developers away from the wild west of GO TO statements and toward proper structured programming.

Take a look at this IF block:

IF WS-ACCOUNT-BALANCE > 1000.00 COMPUTE WS-INTEREST = WS-ACCOUNT-BALANCE * WS-INTEREST-RATE ELSE MOVE 0 TO WS-INTEREST END-IF. The logic is completely self-contained and obvious, thanks to that END-IF. It’s light-years ahead of an older version that would have used GO TO to jump to a different paragraph.

The PERFORM verb is our go-to for loops. You can run them a specific number of times or loop until a condition is met:

PERFORM VARYING I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL I > 10 DISPLAY “Processing record number: ” I END-PERFORM. This modern, structured style is non-negotiable for writing professional-grade COBOL. For really complex programs, getting the initial structure built can feel a bit repetitive. This is where a tool can give you a head start. For example, using a COBOL code generator to scaffold your divisions and data definitions can save a ton of time, freeing you up to focus on the actual business logic.

At its heart, COBOL was built for one thing: chewing through enormous piles of data. That data almost always resides in files, which makes understanding file input/output (I/O) one of the most practical skills you can master. It’s the engine that powers batch processing, generates reports, and updates data in countless enterprise systems that are still running today.

Unlike modern languages where file access is often hidden behind convenient libraries, COBOL makes you be explicit and structured. This isn’t a limitation; it’s a feature. This disciplined approach ensures every single interaction with a file is clearly defined, which is absolutely critical when you’re building reliable, high-volume applications. Let’s walk through the entire lifecycle of managing a file in this tutorial on COBOL.

First things first, you need to build a bridge between your program and the actual data file sitting on the disk. This crucial connection is made in the ENVIRONMENT DIVISION, tucked inside the INPUT-OUTPUT SECTION. You’ll use a SELECT statement to map an internal, logical name for your file to its physical location.

Let’s say you’ve got a file named CUSTOMER.DAT that holds, you guessed it, customer records. Here’s how you’d hook it up:

ENVIRONMENT DIVISION.

INPUT-OUTPUT SECTION.

FILE-CONTROL.

SELECT CUSTOMER-FILE

ASSIGN TO "CUSTOMER.DAT"

ORGANIZATION IS SEQUENTIAL

FILE STATUS IS WS-CUSTOMER-FILE-STATUS.This block might look simple, but it’s doing a lot of heavy lifting:

**SELECT CUSTOMER-FILE**: This creates an internal name (CUSTOMER-FILE) that your program will use from now on to talk about this file.**ASSIGN TO "CUSTOMER.DAT"**: This is the part that links your internal name to the real file on the system. The exact syntax here can change a bit depending on your specific COBOL compiler and operating system.**ORGANIZATION IS SEQUENTIAL**: This tells COBOL how the data is laid out. Sequential files are the most fundamental type; you read records one after the other, from start to finish.**FILE STATUS IS WS-CUSTOMER-FILE-STATUS**: Think of this as your early warning system. You’re designating a variable (WS-CUSTOMER-FILE-STATUS) that will get a two-character code after every single file operation, telling you if it worked or why it failed.Once the file is connected, you have to tell COBOL exactly what the data inside looks like. This happens in the FILE SECTION of the DATA DIVISION. Here, you’ll define a record structure using a File Description (FD) entry that perfectly mirrors the layout of each line in your data file.

Sticking with our customer file example:

DATA DIVISION.

FILE SECTION.

FD CUSTOMER-FILE.

01 CUSTOMER-RECORD.

05 CUST-ID PIC 9(5).

05 CUST-NAME PIC X(30).

05 CUST-BALANCE PIC S9(7)V99.This FD entry for CUSTOMER-FILE is immediately followed by a record layout, which we’ve named CUSTOMER-RECORD. Each field is meticulously defined with a PIC (Picture) clause, making sure your program slices and dices the fixed-format data correctly.

With all the setup out of the way, you’re ready to actually manage the file in your PROCEDURE DIVISION. This follows a very clear, logical lifecycle: open the file, process the records, and then close it. No shortcuts.

The OPEN statement gets the file ready for action. You have to tell it how you want to use the file:

**INPUT**: To read data from a file that already exists.**OUTPUT**: To write data to a brand new file. Be careful—this will create a new file or completely overwrite an existing one.**I-O**: For both reading from and writing to the same existing file (most common with indexed or relative files).**EXTEND**: To tack new records onto the end of an existing sequential file.